OUR Cowichan presents to the CVRD on Wed May 14th 9:30 am

Our youth are suffering - and OUR Cowichan report, and the likelihood of their pilot project to be successful.

This past week, a parent called us to let us know their daughter was having another "episode," one they had seen many times—she was out of control and threatening to kill herself. These parents have literally done everything parents can do, from regular behaviour therapy to natural and allopathic medicines, and many trips to the ER. Knowing that going to the ER would likely be another waste of time but honouring their daughter’s wishes, they went to the Cowichan District Hospital (CDH). What happened next was far from surprising to the parents. After a long wait, a doctor entered their space and bluntly told them there was no child psychologist available and that their daughter should call mental health services during business hours the next day. The parents’ concerns were dismissed, and they were told to deal with the issue the following day during "business hours." The daughter was not eligible for admission because the cut she had given herself was deemed "surface-level and not that deep." This child has special needs.

These parents have also made the long drive to Victoria multiple times after being brushed off at CDH. However, even though they saw a psychiatrist, the visit was very brief, and they were told to return home.

In another story, a parent had a child struggling with addiction. They sought help from Island Health, which offered counselling, but much of it focused on "safe usage" of drugs and the supply of paraphernalia. The child was not eligible for their outreach program because they had a home. Island Health also offered the parent a prescription for the child’s drug of choice if they wished to purchase it for them. This child has also ended up in the hospital after the parent called the RCMP for a wellness check during very volatile times. The child was brought to the hospital but was not seen by a specialist or therapist; instead, they were talked to, and supervised by, the attending officer. The parent expressed gratitude and appreciation for the officers, who were very kind. However, they noted that the time (1–2 hours) the RCMP spent with the child took them away from other calls they might have needed to attend. There is no rehab on the island for youth who are not First Nations, and youth cannot be forced into treatment by their parents. Even when they express a desire to get better, they face a six-month waiting list for rehab on the mainland. Imagine if we redirected the safe supply funding to helping these youth before they become a statistic on the street or in the morgue?

OUR Cowichan has a needs analysis report on their website that is very informative and factual as to many of the missing resources for our youth. This report was funded by Social Planning and Research Council of BC; and Our Cowichan Community Health Network.

In this report, { Full 50 page report can be found HERE } they admitted that there truly is no help for children, especially in the instances shown in the stories above.

“Healthcare: There is no child psychiatrist in the Valley. This represents a significant gap in service. Currently youth in crisis are sent to either Comox or Victoria if they are considered high risk and vulnerable. This removes them from their support systems, isolates them from their community, and makes it difficult to create clear pathways for after care.”

Additionally it noted “Supports for Parents: When you are home because you have to be home as the primary caregiver for a struggling teen, there is very little financial support which adds additional stressors to the family. EI will pay some modest wage for caregivers for some diagnosis but not for others – for instance, diagnosed eating disorders are considered EI eligible for caregivers but suicide attempts are not. Parents who are advocating for their young people are often labeled as ‘crazy’ or ‘aggressive’ or ‘high needs’. This does not help them to do their frontline job and it undermines the ability to get the right/best help to the youth.”

“What the parents had to say: One focus group was held with parents, all of whom responded to a Facebook ad posted by CWHC, and all of whom had had children in the system. The research team fully acknowledges that this is a small and biased sample of experiences, but feels that the perspectives are valid and provide a foundation for examining how services are provided to youth and how families are seen by service providers. The consistent theme from all of the stories is that the parents learned distrust of the system that they thought would help their kids. They felt unsupported at the time of crisis, which (with wait lists, etc.) was an extended time. They felt that their concerns tended to be dismissed, i.e. they were overreacting to normal adolescent behaviours, but in their experience, they had observed behaviour change which were directly linked to a traumatic event in the life of their child, although the trauma was only revealed years later, in some cases. Some services were identified as being very helpful, but even those were criticized for a variety of reasons.” “Parents spoke of the “learned distrust” they now have because, from their perspective, the system failed their youth. When youth are in crisis, families are usually (not always) the first line of support. In general, the parents did not feel supported by the agencies and other caregivers to do the supportive work. Parents need to be trusted that they are recognizing a problem in the moment, rather than having their concerns dismissed. They also need systems navigation support to assist their youth with accessing appropriate”

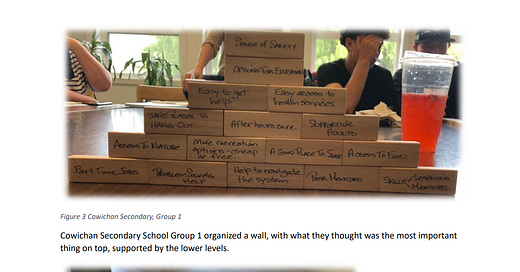

*picture from the report

The following bullet points provide a high level overview of their stories:

MCFD Eating disorder clinic: Free if a youth – amazing support. Year long process/support for most youth and then are ready to transition to a new level of care. Once in remission no continuity of care. Not allowed to continue to see the counsellor who youth had a relationship with. Passed onto different counsellor without proper introductions or handovers. No support through the transition time and not a lot of clarity around ongoing support once age 18.

Hospital experience not positive with suicide attempt: initial support from ER staff ok. Kind, supportive. Put in seclusion room with open door. Mom able to be present. Had necessities: blanket, sheets, water, toilet paper, phone etc. Mom left to go home to shower, change, check in with family; psychiatrist went in and made assessment. All supports taken away, parent not allowed to go in to see child once back, not given water, toilet paper. Nursing staff apologetic but could not change psychiatrist’s orders. Communication between service providers not in place. Transferred to Comox where care much improved. Believe this to be due to staff more in alignment with approach/care.

Once youth was labelled care changed: youth not necessarily believed that what they were experiencing (pain, anxiety, emotions) was real. Youth not trusted and experiences not validated.

Had trauma incident (sexual assault) and behaviours escalated over time. When trauma event was identified (years later, by parent not by service provider) is where change in behaviour happened.

Time as family/mom providing support to child was not supported by a service agency. Supports for mom did not exist. Had to quit job to full-time care for child. Initially able to get EI as homecare provider but following suicide attempt needed to convince GP for ongoing access to regular EI. Felt that in order to get EI coverage had to have their own mental health crisis.

Had trauma incident (sexual assault) and behaviours escalated over time

Access to EFAP-differing number of appointments, depending on the type of service required.

GP not helpful, with no training or background in mental health.

Private counselling very expensive.

Reached out to CVYS, waited 6 weeks for call back after intake. Counsellor not a great fit.

CYMH long wait; took 9 months before seeing counsellor. Had good relationship and then counsellor sent to 100 Mile House.

No psychiatric consult made/available.

Seen in ER following suicide attempt. Discharged after being stitched up (by resident). Did not see ER doc before being sent home. No follow up care plan for wounds. ER knew she had a counselling appointment in 2 weeks and said that would be sufficient follow up.

Long wait before being able to engage or get support within the system despite knowing child had significant issues. Feeling of being super isolated in the system. Hard to feel heard or that concerns were valid.

CWAV parents of youth group who have experienced sexual assault very helpful. Helped reduce feelings of being alone, isolated, and shame.

Parent of struggling youth not supported by GP, Counsellor, Psychiatrist. Major financial implication and emotional and mental impacts when supporting youth.

Had trauma incident and behaviours escalated over time until incident disclosed to sibling.

RCMP office closed at 4pm. Had to stand outside and use their phone to describe sexual assault story. Got a call back at 9pm. Police did provide information regarding Ravens Nest (youth advocacy with legal issues). However, there was a 2-3 month gap between telling story and seeing someone at Raven’s Nest.

Family support available from CWAV and saw counsellor.

GP made pediatric referral which was helpful but no access to child psychiatrist as no one in Duncan offering service, only Victoria.

Identified that it is family connection that is keeping kids alive which is not a fair role to have to have in the system. System not meeting the needs of the kids or the family.

People coming together with lived experience reduces isolation, builds strength and resilience. Knowing that she wasn’t alone changed her perspective, provided strength and courage.

Need to strengthen parents especially mothers as they tend to provide the majority of the emotional support to the children.

Experiencing intergenerational trauma and its impact on children. History of abusive relationship in pregnancy and ongoing in co-parenting relationship. Long story about how an unhealthy relationship between parents can impact child ability to access support. Lack of agreement, power and control dynamics impacts child’s ability to have their needs met.

On wait list age 10 months to 1 year before being able to see counsellor.

Pediatric referral: Youth put on medications with no parental involvement. Parent does not need to know what child has been prescribed at age 14. Difference between medication and mental health needs. System needs to value and understand mental health issues later.”

IF YOU HAVE SIMILAR STORIES, FEEL FREE TO REACH OUT TO contact@coap.ca

Note, also recognized in the report: “ CYMH only sees youth who are very complex and at high risk of harm; YSTAR requires that youth have a substance use issue, in addition to being complex. Only 1 sexual abuse & exploitation worker for the region, with a 4 month wait list. Need one or more psychologists – at this time there is one with responsibility for the region who attends 4 days/month”

“Waitlists, when you are in a crisis, are almost impossible. To be told that you cannot see a counsellor for several months when every minute feels like the last one, is just impossible. There must, somehow be more resources infused into the system – even something like structured group meet-ups so families feel they are not doing it all alone.” – Parent focus group participant

Also the report seemed to a heavily lean towards help for Indigenous, LGBTQ and BIPOC youth. All needed, but once again, puts Caucasian youth who have homes, as the least priority for help/resources.

Interesting quote : “Most Indigenous organizations are not dealing with gender diverse youth because not many Indigenous youth are “out.” This is largely due to the community not being in a space to accept this diversity, which is probably due to colonization.”

OUR Cowichan will be presenting their 2024 year end report to the Board ( Report can be viewed HERE ) They will be presenting their work, and partnerships.

One of the achievements: they have secured is a 4 million dollar pilot project for vulnerable street youth ( funded by The Ministry of Mental Health and Addictions, as well as The Ministry of Children and Family Development) . They have also secured a donation of $450,000 from the Mischa Weisz Foundation and Coldest Nights which allowed the host agency Canadian Mental Health Association to purchase a house and a Van. - Cowichan Green community has been contracted to make the meals - unable to find the contract and cost for this; however in estimating, based on similar programs, meal contracts for youth shelters range from $5–$15 per meal, depending on quality and frequency. For 4–6 youth daily (per YES’s current usage), assuming three meals per day, costs could be $60–$270 daily or $22,000–$99,000 annually. This is a rough estimate, as the contract may include outreach meals for a larger group. Cowichan Green Community could receive administrative fees or overhead (5–10% of the contract value).

“The shelter provides 24/7 services for youth aged 15–18 in crisis or at risk of harm or homelessness, offering wrap-around supports (e.g., mental health, addiction services, life skills) and short-term accommodation (up to two weeks at a time) in a three-bedroom home.

Current Status: As of May 2025, the shelter sees 4–6 youth daily, with expectations of increased usage. Formal day programming is still being developed based on youth feedback. CMHA-CVB and other partners likely receive administrative fees from the $4 million budget.

Statistics on Social Pilot Program Failures

General Trends: A 2019 Stanford Social Innovation Review report estimated that 60–70% of social pilot programs globally, including pay-for-success models, fail to secure long-term funding due to challenges in proving impact or aligning with public sector priorities. While not specific to Canada, this suggests a high risk for programs like Cowichan YES.

Canadian Context: The 2016 Brookings Institution report on Canada’s social innovation ecosystem noted that many pilot programs funded through initiatives like the Investment Readiness Program (2019–2024) struggle to scale, with up to 60% failing to transition to permanent programs due to funding cliffs or weak evaluation.

Youth Programs: The Youth Employment and Skills Strategy (YESS) evaluation (Canada.ca, 2024) reported that only pilots with robust data collection and government commitment achieved sustainability. Many youth-focused pilots fail due to short-term funding cycles (1–3 years), which aligns with the two-year timeline of Cowichan YES.

BC-Specific Insight: The Ministry of Mental Health and Addictions, which funds Cowichan YES, has faced criticism for pilot programs with unclear long-term plans. For example, a 2023 BC Auditor General report on mental health services noted that many pilot initiatives lack sustainable funding models, leading to service gaps when initial grants expire.

BC Youth Homelessness Pilots (Various, 2010s):

Description: Small-scale pilots in BC, such as temporary youth shelters in Vancouver and Victoria, funded by MCFD or local NGOs with budgets of $100,000–$500,000. Outcome: Many closed after 1–2 years due to funding shortages. A 2021 report by The Discourse noted that youth homelessness in Cowichan persisted due to the lack of permanent shelters before YES.

Reason for Failure: Reliance on short-term grants and inability to secure municipal or provincial budgets. Cowichan YES’s $4 million budget is larger, but its two-year timeline poses a similar risk.

Based on the project’s structure and broader trends, here’s an analysis of potential funding sources post-pilot (after 2026, assuming a two-year timeline from June 2024):

Provincial Government (MCFD): Likelihood: Moderate. MCFD is a primary funder and has committed to the YES services model, with Cowichan as the second pilot site. If the pilot demonstrates measurable outcomes (e.g., reduced youth homelessness, fewer ER visits), MCFD may integrate it into its Child and Youth Mental Health (CYMH) budget, which funds clinics across BC.

Challenges: The dissolution of the Ministry of Mental Health and Addictions (noted in) could shift responsibilities to MCFD or Island Health, potentially disrupting funding. Budget constraints or political changes (e.g., a new BC government post-2025) could also limit uptake. Example: Pathways to Education Canada, initially a Toronto pilot, secured $38 million in federal funding (2018–2022) after proving impact. Cowichan YES would need similar evidence to secure MCFD funding.

Federal Government: Likelihood: Low to Moderate. Programs like the Youth Mental Health Fund or Reaching Home (Canada’s homelessness strategy) could provide grants, but these are competitive and typically smaller ($100,000–$1 million). Challenges: Federal funding often requires NGOs like CMHA-CVB to apply repeatedly, diverting resources from service delivery. The pilot’s small scale (three beds) may not attract large federal investments.

Of course the hope is that this project scales way up in nature, and does not prioritize any ethnic groups, and becomes a success - however, the amount of work needed to secure funding, and prove it is a success can also take away from the work needed in the shelter by the NGOs.

Success is always the goal - Success over the mental health and addictions industrial complex however.

Sincerely, Team COAP